Wind wave

In fluid dynamics, wind waves or, more precisely, wind-generated waves are surface waves that occur on the free surface of oceans, seas, lakes, rivers, and canals or even on small puddles and ponds. They usually result from the wind blowing over a vast enough stretch of fluid surface. Waves in the oceans can travel thousands of miles before reaching land. Wind waves range in size from small ripples to huge waves over 30 meters high.[1]

When directly being generated and affected by the local winds, a wind wave system is called a wind sea. After the wind ceases to blow, wind waves are called swell. Or, more generally, a swell consists of wind generated waves that are not—or are hardly—affected by the local wind at that time. They have been generated elsewhere, or some time ago.[2] Wind waves in the ocean are called ocean surface waves.

Tsunamis are a specific type of wave not caused by wind but by geological effects. In deep water, tsunamis are not visible because they are small in height and very long in wavelength. They may grow to devastating proportions at the coast due to reduced water depth.

Contents |

Wave formation

The great majority of large breakers one observes on a beach result from distant winds. Five factors influence the formation of wind waves:[3]

- Wind speed

- Distance of open water that the wind has blown over (called the fetch)

- Width of area affected by fetch

- Time duration the wind has blown over a given area

- Water depth

All of these factors work together to determine the size of wind waves. The greater each of the variables, the larger the waves. Waves are characterized by:

- Wave height (from trough to crest)

- Wavelength (from crest to crest)

- Wave period (time interval between arrival of consecutive crests at a stationary point)

- Wave propagation direction

Waves in a given area typically have a range of heights. For weather reporting and for scientific analysis of wind wave statistics, their characteristic height over a period of time is usually expressed as significant wave height. This figure represents an average height of the highest one-third of the waves in a given time period (usually chosen somewhere in the range from 20 minutes to twelve hours), or in a specific wave or storm system. Given the variability of wave height, the largest individual waves are likely to be about twice the reported significant wave height for a particular day or storm.[4]

Types of wind waves

Three different types of wind waves develop over time:

- Capillary waves, or ripples

- Seas

- Swells

Ripples appear on smooth water when the wind blows, but will die quickly if the wind stops. The restoring force that allows them to propagate is surface tension. Seas are the larger-scale, often irregular motions that form under sustained winds. They tend to last much longer, even after the wind has died, and the restoring force that allows them to persist is gravity. As seas propagate away from their area of origin, they naturally separate according to their direction and wavelength. The regular wave motions formed in this way are known as swells.

Individual "rogue waves" (also called "freak waves", "monster waves", "killer waves", and "king waves") much higher than the other waves in the sea state can occur. In the case of the Draupner wave, its 25 m (82 ft) height was 2.2 times the significant wave height. Such waves are distinct from tides, caused by the Moon and Sun's gravitational pull, tsunamis that are caused by underwater earthquakes or landslides, and waves generated by underwater explosions or the fall of meteorites—all having far longer wavelengths than wind waves.

Yet, the largest ever recorded wind waves are common—not rogue—waves in extreme sea states. For example: 29.1 m (95 ft) high waves have been recorded on the RRS Discovery in a sea with 18.5 m (61 ft) significant wave height, so the highest wave is only 1.6 times the significant wave height.[5] The biggest recorded by a buoy (as of 2011) was 32.3 m (106 ft) high during the 2007 typhoon Krosa near Taiwan.[6]

Wave shoaling and refraction

As waves travel from deep to shallow water, their shape alters (wave height increases, speed decreases, and length decreases as wave orbits become asymmetrical). This process is called shoaling.

Wave refraction is the process by which wave crests realign themselves as a result of decreasing water depths. Varying depths along a wave crest cause the crest to travel at different speeds, with those parts of the wave in deeper water moving faster than those in shallow water. This process continues until the crests become parallel to the depth contours and/or the wave breaks. Orthogonals (lines normal to wave crests between which a fixed amount of energy is contained) converge on headlands and diverge in bays. Therefore, wave energy is concentrated on headlands but is dissipated in bays, with resulting increase in wave height at headlands and decrease in bays.

When breaking occurs before the refraction process is complete, Longshore drift may occur, often causing a redistribution of sediment from headlands to bays.

Wave breaking

Some waves undergo a phenomenon called "breaking". A breaking wave is one whose base can no longer support its top, causing it to collapse. A wave breaks when it runs into shallow water, or when two wave systems oppose and combine forces. When the slope, or steepness ratio, of a wave is too great, breaking is inevitable.

Individual waves in deep water break when the wave steepness—the ratio of the wave height H to the wavelength λ—exceeds about 0.17, so for H > 0.17 λ. In shallow water, with the water depth small compared to the wavelength, the individual waves break when their wave height H is larger than 0.8 times the water depth h, that is H > 0.8 h.[7] Waves can also break if the wind grows strong enough to blow the crest off the base of the wave.

Three main types of breaking waves are identified by surfers or surf lifesavers. Their varying characteristics make them more or less suitable for surfing, and present different dangers.

- Spilling, or rolling: these are the safest waves on which to surf. They can be found in most areas with relatively flat shorelines. They are the most common type of shorebreak

- Plunging, or dumping: these break suddenly and can "dump" swimmers—pushing them to the bottom with great force. These are the preferred waves for experienced surfers. Strong offshore winds and long wave periods can cause dumpers. They are often found where there is a sudden rise in the sea floor, such as a reef or sandbar.

- Surging: these may never actually break as they approach the water's edge, as the water below them is very deep. They tend to form on steep shorelines. These waves can knock swimmers over and drag them back into deeper water.

Science of waves

Wind waves are mechanical waves that propagate along the interface between water and air; the restoring force is provided by gravity, and so they are often referred to as surface gravity waves. As the wind blows, pressure and friction forces perturb the equilibrium of the water surface. These forces transfer energy from the air to the water, forming waves. The initial formation of waves by the wind is described in the theory of Phillips from 1957, and the subsequent growth of the small waves has been modeled by Miles, also in 1957.[8][9]

In the case of monochromatic linear plane waves in deep water, particles near the surface move in circular paths, making wind waves a combination of longitudinal (back and forth) and transverse (up and down) wave motions. When waves propagate in shallow water, (where the depth is less than half the wavelength) the particle trajectories are compressed into ellipses.[10][11]

As the wave amplitude (height) increases, the particle paths no longer form closed orbits; rather, after the passage of each crest, particles are displaced slightly from their previous positions, a phenomenon known as Stokes drift.[12][13]

For intermediate and shallow water, the Boussinesq equations are applicable, combining frequency dispersion and nonlinear effects. And in very shallow water, the shallow water equations can be used.

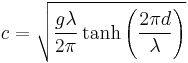

As the depth below the free surface increases, the radius of the circular motion decreases. At a depth equal to half the wavelength λ, the orbital movement has decayed to less than 5% of its value at the surface. The phase speed of the surface wave (also called the celerity) is well approximated by

where

- c = phase speed;

- λ = wavelength;

- d = water depth;

- g = acceleration due to gravity at the Earth's surface.

In deep water, where  , so

, so  and the hyperbolic tangent approaches

and the hyperbolic tangent approaches  , the speed

, the speed  , in m/s, approximates

, in m/s, approximates  , when

, when  is measured in metres. This expression tells us that waves of different wavelengths travel at different speeds. The fastest waves in a storm are the ones with the longest wavelength. As a result, after a storm, the first waves to arrive on the coast are the long-wavelength swells.

is measured in metres. This expression tells us that waves of different wavelengths travel at different speeds. The fastest waves in a storm are the ones with the longest wavelength. As a result, after a storm, the first waves to arrive on the coast are the long-wavelength swells.

When several wave trains are present, as is always the case in nature, the waves form groups. In deep water the groups travel at a group velocity which is half of the phase speed.[14] Following a single wave in a group one can see the wave appearing at the back of the group, growing and finally disappearing at the front of the group.

As the water depth  decreases towards the coast, this will have an effect: wave height changes due to wave shoaling and refraction. As the wave height increases, the wave may become unstable when the crest of the wave moves faster than the trough. This causes surf, a breaking of the waves.

decreases towards the coast, this will have an effect: wave height changes due to wave shoaling and refraction. As the wave height increases, the wave may become unstable when the crest of the wave moves faster than the trough. This causes surf, a breaking of the waves.

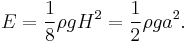

The movement of wind waves can be captured by wave energy devices. The energy density (per unit area) of regular sinusoidal waves depends on the water density  , gravity acceleration

, gravity acceleration  and the wave height

and the wave height  (which, for regular waves, is equal to twice the amplitude,

(which, for regular waves, is equal to twice the amplitude,  ):

):

The velocity of propagation of this energy is the group velocity.

Wind wave models

Surfers are very interested in the wave forecasts. There are many websites that provide predictions of the surf quality for the upcoming days and weeks. Wind wave models are driven by more general weather models that predict the winds and pressures over the oceans, seas and lakes.

Wind wave models are also an important part of examining the impact of shore protection and beach nourishment proposals. For many beach areas there is only patchy information about the wave climate, therefore estimating the effect of wind waves is important for managing littoral environments.

See also

Notes

- ^ Tolman, H.L. (2008), "Practical wind wave modeling", in Mahmood, M.F., CBMS Conference Proceedings on Water Waves: Theory and Experiment, Howard University, USA, 13–18 May 2008: World Scientific Publ., (in press), ISBN 978-981-4304-23-8, http://polar.ncep.noaa.gov/mmab/papers/tn270/Howard_08.pdf

- ^ Holthuijsen (2007), page 5.

- ^ Young, I. R. (1999). Wind generated ocean waves. Elsevier. ISBN 0080433170. p. 83.

- ^ Weisse, Ralf; von Storch, Hans (2008). Marine climate change: Ocean waves, storms and surges in the perspective of climate change. Springer. p. 51. ISBN 9783540253167.

- ^ Holliday, Naomi P.; Yelland, Margaret J.; Pascal, Robin; Swail, Val R.; Taylor, Peter K.; Griffiths, Colin R.; Kent, Elizabeth (2006), "Were extreme waves in the Rockall Trough the largest ever recorded?", Geophysical Research Letters 33 (L05613), Bibcode 2006GeoRL..3305613H, doi:10.1029/2005GL025238

- ^ P. C. Liu; H. S. Chen; D.-J. Doong; C. C. Kao; Y.-J. G. Hsu (11 June 2008), "Monstrous ocean waves during typhoon Krosa", Annales Geophysicae (European Geosciences Union) 26: 1327–1329, doi:10.5194/angeo-26-1327-2008, http://www.ann-geophys.net/26/1327/2008/angeo-26-1327-2008.pdf

- ^ R.J. Dean and R.A. Dalrymple (2002). Coastal processes with engineering applications. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-60275-0. p. 96–97.

- ^ Phillips, O. M. (1957), "On the generation of waves by turbulent wind", Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2 (5): 417–445, Bibcode 1957JFM.....2..417P, doi:10.1017/S0022112057000233

- ^ Miles, J. W. (1957), "On the generation of surface waves by shear flows", Journal of Fluid Mechanics 3 (2): 185–204, Bibcode 1957JFM.....3..185M, doi:10.1017/S0022112057000567

- ^ For the particle trajectories within the framework of linear wave theory, see for instance:

Phillips (1977), page 44.

Lamb, H. (1994). Hydrodynamics (6th edition ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521458689. Originally published in 1879, the 6th extended edition appeared first in 1932. See §229, page 367.

L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz (1986). Fluid mechanics. Course of Theoretical Physics. 6 (Second revised edition ed.). Pergamon Press. ISBN 0 08 033932 8. See page 33. - ^ A good illustration of the wave motion according to linear theory is given by Prof. Robert Dalrymple's Java applet.

- ^ For nonlinear waves, the particle paths are not closed, as found by George Gabriel Stokes in 1847, see the original paper by Stokes. Or in Phillips (1977), page 44: "To this order, it is evident that the particle paths are not exactly closed … pointed out by Stokes (1847) in his classical investigation".

- ^ Solutions of the particle trajectories in fully nonlinear periodic waves and the Lagrangian wave period they experience can for instance be found in:

J.M. Williams (1981). "Limiting gravity waves in water of finite depth". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A 302 (1466): 139–188. Bibcode 1981RSPTA.302..139W. doi:10.1098/rsta.1981.0159.

J.M. Williams (1985). Tables of progressive gravity waves. Pitman. ISBN 978-0273087335. - ^ In deep water, the group velocity is half the phase velocity, as is shown here. Another reference is [1].

References

Scientific

- Stokes, G.G. (1847). "On the theory of oscillatory waves". Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 8: 441–455.

Reprinted in: G.G. Stokes (1880). Mathematical and Physical Papers, Volume I. Cambridge University Press. pp. 197–229. http://www.archive.org/details/mathphyspapers01stokrich. - Phillips, O.M. (1977). The dynamics of the upper ocean (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 29801 6.

- Holthuijsen, Leo H. (2007). Waves in oceanic and coastal waters. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521860288.

- Falkovich, Gregory (2011). Fluid Mechanics (A short course for physicists). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00575-4.

- Janssen, Peter (2004). The interaction of ocean waves and wind. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521465403.

Other

- Rousmaniere, John (1989). The Annapolis Book of Seamanship (2nd revised ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671674471.

- Carr, Michael (Oct 1998). "Understanding Waves". Sail: 38–45.

External links

- "Anatomy of a Wave" Holben, Jay boatsafe.com captured 5/23/06

- Fluid Mechanics website with movies, Q&A etc

- NOAA National Weather Service

- ESA press release on swell tracking with ASAR onboard ENVISAT

- Introductory oceanography chapter 10 - Ocean Waves

- HyperPhysics - Ocean Waves

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||